Q+A With Charles Bamforth: The Professor of Beer

This article was originally published on Gourmet.com in 2008.

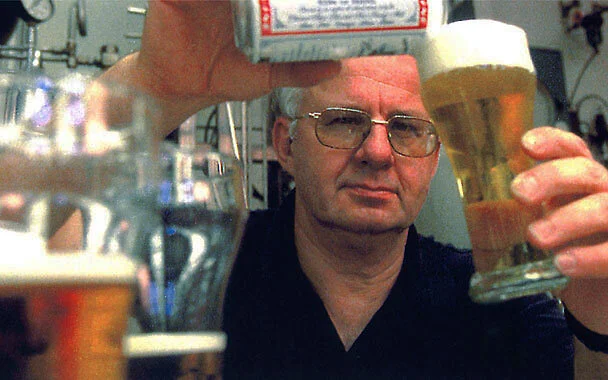

Call Charles Bamforth a beer evangelist. For 30-plus years, the British-born professor has obsessed about suds, spending the early years of his career toiling as a yeast researcher and overseeing quality assurance at a Bass brewery. He currently—and perhaps ironically—works at a famed winemaking school: the University of California at Davis. In addition to serving as chairman of the department of food science and technology, Bamforth is the Anheuser-Busch Endowed Professor of Brewing Science, overseeing one of the only university-accredited brewing programs in the U.S. (the other is at Oregon State; trade schools also offer brewing courses). The professor of beer, who pitted wine against beer in his recent book Grape vs. Grain, talked with Joshua M. Bernstein about the problem with insanely hoppy beers; brewers’ biggest mistake; and why restaurateurs should be sent to Belgium.

**

Joshua M. Bernstein: Tell us about your three beer-centric classes.

Charles Bamforth: Introduction to Beer and Brewing discusses the history of beer, the business of brewing and basic science. In Malting and Brewing Science, I teach the detailed science and technology of brewing. Beer is sublime biochemistry, and to understand what you’re doing you have to understand the science. In Practical Malting and Brewing, students make a low-bitterness beer called Aggie’s Ale—named after the Davis mascot—then tweak that to understand the impact of, say, changing hops’ strength. Lastly, they design weird and wonderful beers.

JMB: What do they make?

CB: I tell my students the hardest beers to make are the gentlest, because you can’t mask defects. So students make the darkest, hoppiest beer possible. Beers such as North American lagers have relatively subtle flavors. As a consequence, any defects are more glaring in those beers than in very heavily flavored beers, such as stouts. This is why freshness is so important in North America—aging characteristics like cardboard will display themselves most obviously in a North American lager. It is a tribute to the excellence of North American brewers that their beers are so fresh.

JMB: Can beers be too bold?

CB: Outrageously hoppy beers are too challenging to drink because they’re too bitter—a beer should have drinkability. When you sip it you should think, Wow, I enjoyed that. I should have another one.

JMB: Do you convert any wine students to brewing?

CB: I pride myself on converting at least one winemaker a year to the noble beverage. There’s a charm to Sonoma and the Napa Valley, but charm only goes so far. With a greater range of raw materials, plus a seasonal rotation of styles, making beer is much more complicated and rewarding than making wine. I jokingly tell students, “You only have red, white, and pink wine, but there are endless varieties of beer.”

JMB: How else do wine makers and brewers differ?

Brewers tend to use unappealing terms like catty, grainy and burnt, while wine guys tend to use more charming terms, like fruity. If brewers can learn some of the lexicon, we can make some of the terms more appealing. For instance, I don’t think catty is very attractive. When beer ages, it can develop a tomcat-urine flavor. Instead of saying, “This beer tastes like tomcat urine,” perhaps we can substitute the more appealing and equally accurate, “This beer tastes like black-currant buds.”

JMB: What’s home brewers’ biggest mistake?

CB: The golden rule is hygiene, hygiene, hygiene. Brewing equipment must be scrupulously clean. I’m also a great believer in using high-quality yeast. The yeast impacts beer quality through a direct influence on flavor. For example, fruity aromas due to esters come from the yeast. From experience, the liquid forms of yeast give the best performance.

JMB: What are new developments in brewing?

CB: We’re devising newer, more efficient methods of extracting malt from barely, and we’re working on minimizing oxygen exposure throughout the process. That’s the biggest challenge.

JMB: Why?

CB: Most beers are best when they’re first bottled, after which they deteriorate due to oxygen’s presence. To maximize shelf life, keeping the oxygen level low is very important. Using stabilizers like sulfites is the easy solution, but some brewers are reluctant to use stabilizers. They’re keen on the product’s purity.

JMB: Can beer pairings compete with wine pairings at restaurants?

CB: I recently ordered a beer at a New Orleans restaurant, and it was delivered without a glass. It’s amazing how little servers know about beer. They’ll pour it gently to avoid foam—but beer drinkers want foam! How much is too much depends on where you are. If you are in Amsterdam’s Airport Schiphol, chances are that half the beer glass comprises foam—which is too much for me, but they like it that way. If you are in London drinking cask ale, you’re likely to get virtually no foam. The same beer in the north of England will have an inch of foam. Wine’s theater is quite famous, but there’s an equal opportunity with beer. With foam, clarity and color, you can make beer a visual display. We need to ship restaurateurs over to Belgium so they can see the reverence in which beer is held.

JMB: What’s beer’s biggest public-relations problem?

CB: There’s been too much trivializing of beer, in the men-behaving-badly kind of way. Most beer advertising is targeted at that sector—men in the 21-to-30 age bracket who drink the most beer. I get it! And so I rejoice in programs such as [Anheuser-Busch’s] Here’s to Beer campaign, where there is a broader celebration of beer for its provenance and all-round excellence. There are wonderful beers available, and I feel it’s up to the brewers, not just the beer drinkers, to celebrate them. Beer needs to be put on a higher pedestal and take itself with more respect.